Benefits of Tai Chi

Regular practice of Tai Chi can develop:

- Improved overall health

- Calmness and focus of mind

- Increased energy

- Suppleness, strength, co-ordination, balance, and agility

- Relaxation and freedom from stress

- Strengthening of the internal functions of the body

- Boosting of the immune and cardiovascular systems

- Improvement of the body's metabolic functions

- Understanding of the body's processes and self-healing

- Harmony with the natural laws of human life

Tai Chi is a subtle blend of the most refined medical, meditative and martial knowledge combining self-discipline, graceful movement and effortless power.

Students develop increasing physical and mental skills, as awareness and understanding of all aspects of their self increases. You can learn and practise Tai Chi at your individual pace, and, as there are ever-new levels, throughout the rest of your life. These disciplines rely on a mindful re-discovery of the body to enrich and inspire one’s experience of any aspect of life.

A Noble History

Throughout history, Tai Chi has been used by Chinese scholars, monks, sages, artists, intellectuals, emperors and their imperial guards, princes and commoners, because of its extraordinary versatility and proven effectiveness.

Whilst drawing from all the strands of Chinese spiritual and philosophical thought, Tai Chi is not tied to any religion or dogma, but is available to any interested student.

Practitioners of yoga, dance or other martial arts often find that the internal and flowing approach of Tai Chi perfectly complements their own training.

How is Tai Chi Practised?

Tai Chi consists of ‘Four Pillars’ or types of practice, as well as a variety of physical exercises and meditative practices. The Four Pillars are Qigong, Form, Pushing Hands and Application.

Each Pillar develops the ability to coordinate the body, internal energy, and sensitivity to oneself, the space around, and other people, to a higher degree.

Initially many movements focus on gently opening and stretching the joints and muscles of the body,releasing tension that has often been there for years. By increasing the flow of blood and energy, they help to fully nourish all parts of the body. Many of our students report that they feel very relaxed and energised after a session of Qigong, and that they sleep very deeply that night!

Form

This is a flowing sequence of movements, lasting from 5 to 20 minutes. The Form very effectively develops physical skill and health and constitutes a very enjoyable kind of moving meditation. Each movement can be practised at increasing levels of depth as the student develops. There are many variations of the Form within the different Tai Chi lineages and their schools, but they are all derived from the same original Form, and the principles of movement are always the same.

Application

Application is the most advanced aspect of physical training and in some ways the most rewarding. In application the student explores the deeper subtleties of the Form’s movements, in a dynamic fashion with a training partner. Applications test and perfect students’ understanding of the movements, developing high levels of mind-body coordination, awareness, sensitivity, and confidence.

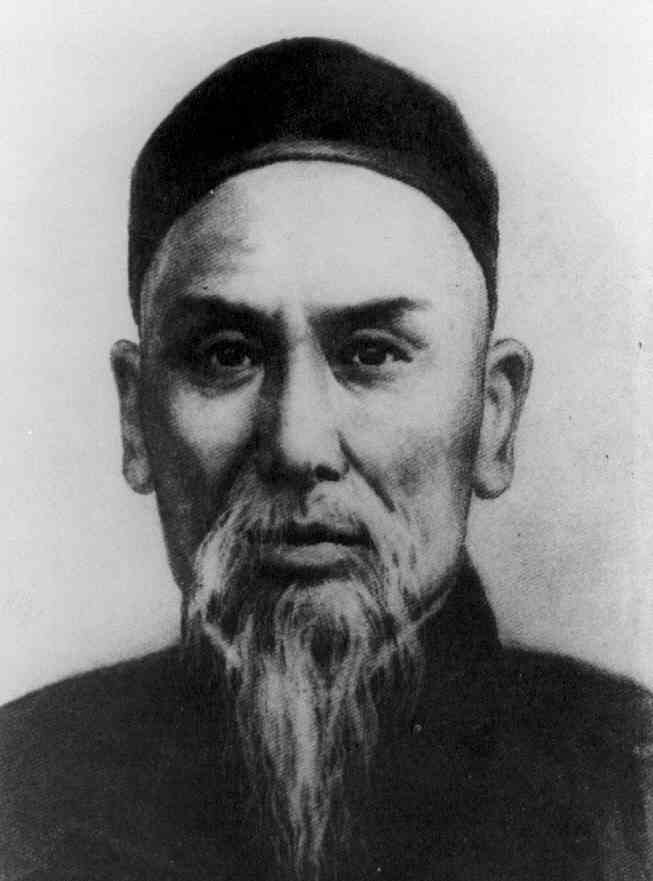

Yang Luchan

楊露禪 (1799–1872) – The bringer of Tai Chi to the world.

One remarkable man brought Tai Chi to the world: a man of such extraordinary qualities that he rose from child servant to companion of the imperial family; became the adopted scion and representative of the quintessence of Chinese knowledge at a time when it was forbidden to any outsider; defeated the highest opponents in the land with such paramount skill and diplomacy that they came, un-humiliated, to learn from him; and unlocked for the whole world this most secret of knowledge.

He was a native of the Yongnian District, in Hebei Province. His family name of Yang, meaning ‘poplar tree’, symbolises outstanding morality and uprightness; his given name, Luchan, prophetically, means ‘the dew of profound meditation’. Born into very poor circumstances, as a young boy he was immersed in the Shaolin martial arts, and when he saw a pharmacy owner in his hometown display remarkable and effortless martial skills in dealing with an aggressive customer, he asked to learn from the man. Recognising Luchan’s sincerity and uprightness, the pharmacy owner told him that he was also house teacher to the sons of a great master, Chen Changxin, in his home town in Henan province. He was sent as a servant to the Chen household, where the Chen family art was taught as the exclusive preserve of the clan / family members, only taught in the dark of night within the walls of the family courtyard.

One version tells that for this reason Luchan was not allowed to learn the art, and so he would spy through a gap in the courtyard wall, then practise alone in his room. Eventually he was caught and was ordered to demonstrate what he had learnt against the senior students. Master Chen was deeply impressed by the skill with which he bested them; he chose to reward his genius by teaching him, and so adopted him into the family so that he might learn the secretive family art

Under the tutelage of Chen Changxin, he trained continuously and assiduously for six years, then returned to Yongnian, where he was challenged to a duel and defeated.

He returned to the Chen village for a further six years, returning again to Yongnian during the Chinese New Year, only to be challenged again by a highly skilled martial artist. The match concluded with a draw and Luchan felt he must return for a further six years

This deeply moved Chen, and he decided to teach him the whole of his art.

Luchan was never satisfied with his skill; he continued to study and research until his knowledge and skill brought him great fame. The art he taught, honed and developed by his unrelenting determination to learn to an unprecedented level, now became known as Huaquan (the martial art of neutralisation) and Mianquan (the martial art of cotton-like softness).

Three brothers, scholars of an aristocratic family, invited Luchan to the court at Beijing, where he was asked to become teacher to the princes, and to the Emperor’s personal guards, the Manchu Banner Battalion.

Luchan sought to test his skills against the highest all over the land, travelling extensively. The invitation to be official instructor to the imperial family was humbling to those who were ousted, and he became a target for challenges by would-be usurpers and the embittered old guard; but although he had to endure endless challenges, his mastery was such that he could neutralise any offensive without harming his opponent. He would find a way to defeat the opponent with such invisible grace that the defeat would not humiliate the challenger; and with great delicacy of word he would belittle his own victories to save the face of his foe, in accord with the highest ethical precepts of traditional Chinese chivalry.

He came to be known by the sobriquet of Yang Wudi 'Yang the Unsurpassable'. In the court at Beijing, the art he taught was finally given the name of Taijiquan ‘the martial art of the supreme ultimate’ by a poet who observed a demonstration of Luchan’s ability.