Yin and Yang: A Philosophy of change

Many books may describe yin and yang in terms of opposites, and list things that are yin or yang. However to grasp their essential meaning it is necessary to stop thinking about the world in terms of static descriptions and labels, and instead adopt a way of thinking which sees the world in a state of constant change. Rather than labelling fixed identities, notions of yin and yang in Chinese thought explain what type of change something is undergoing: is it in a phase of expansion, when something is growing, becoming more active, with more movement (yang), or is it in a phase of contraction, slowing down, reducing, becoming calmer (yin)?

Yin and Yang in nature

In the natural world these changes are immediately apparent. Over a 24-hour period, for example, there are some obvious yin and yang changes. When the sun rises we are in a yang phase of growing activity. This continues until midday, the peak of warmth and movement, after which the day starts to slow, quieten and cool. This is the beginning of the yin phase, culminating in the depths of night, when nature sleeps. Then slowly, as nature wakes up again, we return to the yang phase.

This alternation of yin and yang phases is also apparent over larger time periods, for example in a year, when the seasons take us through the same yin/yang pattern. Over the course of a month it might be slightly less obvious but still just as real. The phases of the moon follow a pattern of waxing and waning, which have a strong effect on the rest of nature.

In more traditional societies, this cycle is absolutely obvious to people. When there is no electricity, the rhythms of the day naturally dictate the rhythms of people's activities, and the lunar cycle is taken as a basic division of time. In primarily agricultural societies, everyone is aware of the cycle of nature, and of the necessity to adapt to it to ensure the best possible harvest.

Studying yin and yang is a way of understanding these ever-changing cycles, and not only in nature. Everything – people's lives, ideas, the world economy – is subject to the basic cycles of the universe, the laws of growth and decay.

The Yin-Yang diagram, or 'Taijitu'

The principles of yin and yang are commonly represented as the famous symbol of a circle consisting of one white and one black half, both swirling around and merging into each other. This is one of the many variations of this ancient symbol.

It is also commonly described as showing "two fishes", one black and one white, with the eye of each fish being the colour of the other. Fish are a very important symbol in Chinese culture and carry many important connotations: they represent harmony, unity and abundance as fish effortlessly swim through water and multiply rapidly. Furthermore, legend has it that carp, with their dragon-like scales and whiskers, have the potential to turn into real dragons and therefore also represent great power and strength.

Both of these aspects refer to qualities found in nature and the natural rhythms of the world – harmony and peace (inwards direction – yin phase) and power and movement (outwards direction – yang phase). It is not surprising that the yin-yang symbol was, amongst other things, traditionally used as a protective amulet. It still can be seen on the ridgepoles of old Chinese bridges and other constructions at the mercy of the cycles of nature.

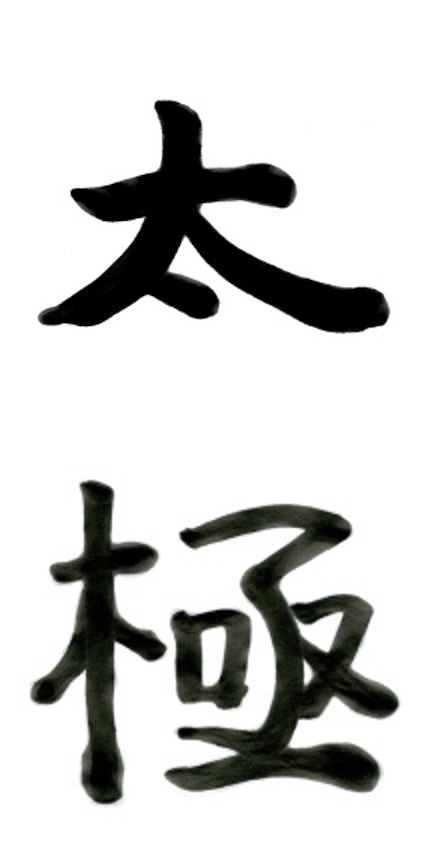

However the most common name of this symbol, and this may come as a surprise to many who read this, is the taiji. This is written in Chinese with the two separate characters, tai and ji.

Tai is often translated as "supreme", meaning "above all else".

Ji is often translated as "ultimate", and refers to the idea of an ultimate extremity or polarity. Together, they form taiji, the two polarities which govern all else, a poetic but nonetheless accurate description of yin and yang.

From Taiji to Taijiquan: Yin and Yang in Tai Chi

If we now add a third character to this, quan, meaning "fist" or, by extension, martial art, we obtain Taijiquan. This is the full name of the art that we study at Mei Quan, and its name can accurately be rendered as "the martial art which embodies the principles of yin and yang". A significant part of Tai Chi is therefore to study yin and yang and understand what they truly mean so that we can use them practically. Understanding opening and closing, increasing speed and slowing down, attacking and retreating allows us achieve true yin, or great stillness, and true yang, or great power.

Perhaps it is now a good time to introduce the concept of Tong Jia Zi. Under this convention, words in Chinese that share similar sounds can share meaning. The word Xi, very close in sound to Qi, carried the meaning of nourishment. The fact that these two concepts were becoming one is evidenced by the fact that the symbol for rice, Mi was now added to the glyph for Qi.

So now, the symbol for Qi is taking on its modern, familiar form. By the second century AD, it is considered to have the qualities of an essential nutritive substance, and it is also worth considering that the word meaning to eat is Chi: another very similar sound.